Over the first 17 years

of Walter Johnson's amazing career, which had begun in 1907, he had

established himself as perhaps baseball's most dominating pitcher. Playing

for the Washington Senators, Johnson had paced the American League in

strikeouts 11 times, wins 5 times, E.R.A. 4 times, complete games 6 times,

innings pitched 6 times and shutouts 6 times. Johnson, known as "The Big

Train," amassed these incredible statistics while playing for a Washington

franchise that was at times so pathetic, fans across the country used to

joke, "Washington, first in war, first in peace, and last in the American

League." Over the first 17 years

of Walter Johnson's amazing career, which had begun in 1907, he had

established himself as perhaps baseball's most dominating pitcher. Playing

for the Washington Senators, Johnson had paced the American League in

strikeouts 11 times, wins 5 times, E.R.A. 4 times, complete games 6 times,

innings pitched 6 times and shutouts 6 times. Johnson, known as "The Big

Train," amassed these incredible statistics while playing for a Washington

franchise that was at times so pathetic, fans across the country used to

joke, "Washington, first in war, first in peace, and last in the American

League."

Washington had twice finished in second place (in 1912 and 1913) but, despite Johnson's dominance on the mound, the Senators had never captured a pennant. Throughout his career Johnson had endeared himself to baseball's fans with his sheer talent and gentlemanly demeanor. Where the fans despised Detroit's unruly Ty Cobb, they respected and admired the team-minded Johnson. Entering the 1924 season, The Big Train seemed to be running out of steam. He failed to post a 20-win season for the first time since 1919, and his strikeout totals were tailing off. Johnson publicly state that his only disappointment was that he had not played in, let alone won, a World Series. Johnson knew his chances were fading. But in 1924, after announcing that the season would be his last, The Big Train was back on track (sorry about the puns). A determined Walter Johnson led the league in wins (23-7), E.R.A (.272), strikeouts (158), shutouts (6) and took the Washington Senators to their first American League flag. After 18 years, Walter Johnson was finally going to play in a World Series. The opponent would be the New York Giants. Johnson was named to start the opener. The score was tied after nine innings, 2-2. Johnson shut down the Giants in the 10th and 11th innings, but then allowed two more runs on a bases-loaded single in the 12th. The Senators managed a run of their own in the bottom of the 12th, but Johnson took the lose, 4-3. The series was knotted at two games apiece when Johnson again took the mound as the game five starter. Johnson was tagged for 13 hits as he suffered his second defeat, 6-2. Johnson was inconsolable. He sat quietly on the Senators' bench as his teammates rallied to claim game six and force the decisive seventh game. The Giants were holding onto a 3-1 eighth inning lead when, as a precautionary measure, Washington's player-manager, Bucky Harris, told Johnson to go warm up in the bullpen. The Senators had two men on base after Muddy Ruel collected his first Series hit. With two outs, Harris hit a grounder to third that took a bad hop over the head of the Giants' 18-year-old third baseman, Freddy Lindstrom (the youngest player ever to appear in a World Series), and two runs scored to tie the game. After the third out was made, Harris signaled for Walter Johnson to enter the game. The chance to achieve his lifelong dream of playing on a World Series Champion was now in his seasoned hands. After retiring the first Giants' batter, Johnson surrendered a triple to Frank Frisch, but settled down to retire the side with the runner stranded. In the 11th, New York put two men on base, but again, Johnson worked his way out of the jam. After the last out in the 12th inning, Johnson had worked four innings of relief. He had allowed six men to reach base, but had fanned five to keep the runners from scoring. With one out in the bottom of the 12th, Washington's Muddy Ruel hit what looked to be a sure out as he popped up to the catcher in foul territory, but New York catcher Hank "Twinkle Toes" Gowdy tossed aside his catcher's mask and then, inextricable, stepped in it. With his foot stuck in the mask, Gowdy stumbled about and the ball fell to the ground. Ruel made the most of his second chance and ripped a double passed third on the next pitch. The next batter in the Washington lineup was Walter Johnson. Manager Harris decided against a pinchhitter and left Johnson to hit. The Big Train hit a grounder to Giant shortstop Travis Jackson. Jackson fumbled the ball and Johnson was safe at first, with Ruel holding at second. Then lightning appeared to strike twice. According to historian Fred Lieb, "All the gremlins and other little imps were working for Washington." Rookie Senators' outfielder, Earl McNeely, who had been 5 for 26 (.192) in the Series, ripped a grounder to Giants' third baseman Freddy Lindstrom, but the ball took a bad hop right over Lindstrom's head-AGAIN-and Ruel raced around the bases to score the winning run. Johnson had a title. Walter Johnson decided to return for the 1925 season, which would be his last. He again led the Senators to the Series, but this time, the gremlins stayed home and the Senators lost to the Pittsburgh Pirates in seven games. Johnson won two games, including a game 4 shutout, but lost the deciding seventh game. |

It was the fourth game of

the 1929 World Series. The Philadelphia Athletics were getting spanked by

the visiting Chicago Cubs. Heading into the bottom of the seventh inning,

the Cubs held a seemingly insurmountable 8-0 lead-a more than adequate

lead for most teams, but we are talking about the Cubs. It was the fourth game of

the 1929 World Series. The Philadelphia Athletics were getting spanked by

the visiting Chicago Cubs. Heading into the bottom of the seventh inning,

the Cubs held a seemingly insurmountable 8-0 lead-a more than adequate

lead for most teams, but we are talking about the Cubs.

Over the first six inning the Athletics had managed only three hits off of Cubs starter Charlie Root. So when none other than our hero, "Bucketfoot" Al Simmons, led off the bottom of the seventh with a truly monstrous home run that landed on the roof of Shibe Park's left field stands, there appeared to be little cause for alarm in the Cubbies dugout: 8-1. The next batter, first baseman Jimmie Foxx, lined a single through the infield. Right fielder Bing Miller then popped what looked like a routine fly ball into center field. Cub center fielder Louis "Hack" Wilson converged on the ball but lost it in the bright sun (yes, they used to play the World Series during the day) and the ball fell in for a single. Third baseman Jimmy Dykes followed with a single that drove in Foxx: 8-2. Connie Mack, sensing that Root was tiring, reasoned that the Chicago ace would start to groove his pitches and instructed his batters to "swing at everything." Shortstop Joe Boley responded with a single to drive in Miller: 8-3. A pop to short by the next batter, George Burns only provided a false sense of security for the Cubs. The next batter, Max Bishop, lined a single over Root's head to drive in Dykes: 8-4. Chicago manager Joe McCarthy had seen enough. Veteran pitcher Art Nehf was summoned from the bullpen. When Nehf arrived at the mound, McCarthy should have sent him out to center field. The first batter to face Nehf was Mule Haas. Haas smashed a shot to center field. Again, Cub center fielder Hack Wilson lost the ball in the sun, but this time the ball sailed well over Wilson's head. By the time Wilson chased down the ball in the cavernous Shibe Park center field, Haas had raced around the bases with a three run inside-the-park home run: 8-7. Mickey Cochrane drew a walk and McCarthy went to the bullpen again. This time he called upon John "Sheriff" Blake to face Simmons. Bad call. Al "Bucketfoot" Simmons fears no man-badge or no badge. Simmons ripped the Sheriff's first pitch down the third base line. Then, just as Chicago third baseman Norm McMillan reached for the ball, the ball took an unexplainable, wicked hop over his head. Simmons had a single and the world had futher proof that the Good Lord was rooting for "Bucketfoot" Al Simmons. Foxx then smacked his second hit of the inning and Cochrane came around to score the tying run: 8-8. A stunned McCarthy called for his fourth pitcher of the inning, Pat Malone. Malone proved about as effective as his predecessors to the mound as he quickly beaned Bing Miller and then gave up a two-run double to Dykes: 10-8. Boley and George Burns were then retired to end the inning. The ten runs established the record for the most runs scored in a single World Series inning (equaled by Detroit in the third inning of game 6 in 1968). The eight run deficit which the Athletics overcame remains the largest comeback in Series history. |

The New York Yankees

were facing the Brooklyn Dodgers for the sixth time in the Fall Classic

and, with the series knotted at two games apiece, Yankee Stadium was

packed to the rafters for game five. Don Larsen was on the hill for the

Yanks and Sal "The Barber" Maglie was starting for The Bums. The New York Yankees

were facing the Brooklyn Dodgers for the sixth time in the Fall Classic

and, with the series knotted at two games apiece, Yankee Stadium was

packed to the rafters for game five. Don Larsen was on the hill for the

Yanks and Sal "The Barber" Maglie was starting for The Bums.

Yankee center fielder Mickey Mantle's solo shot in the fourth broke up the scoreless tie and provided Larsen all the run support he would need. At this point, Larsen had faced the entire Dodger starting lineup without allowing a base runner. In the sixth, Yankee right fielder Hank Bauer's singled scored third baseman Andy Carey with an insurance run. Larsen had retired all 15 Dodger batters he had faced. Larsen entered the ninth having retired the first 24 Brooklyn batters in order. With Yogi Berra crouched behind the plate, Dodger right fielder Carl Furillo stepped into the batter's box and quickly flied out to Bauer: 25 straight. Brooklyn catcher Roy Campanella had connected for 20 home runs during the season but, with Larsen absolutely dominating the game, Campanella grounded weekly to Yankee second baseman Billy Martin: 26 straight. Maglie, who had only managed to hit .129 in the regular season, was due to bat next. Brooklyn manager Walter Alston sent Dale Mitchell in to pinch hit for The Barber. Mitchell was in the final season of an 11 year career which had been spent entirely with the Cleveland Indians, before Mitchell was sold to Brooklyn on July 29 of 1956. Mitchell had compiled a .312 career average, and had batted .292 in 19 games for Brooklyn. Larsen's first pitch to Mitchell sailed outside: 1-0. The second pitch was in for a called strike: 1-1. Mitchell swung at Larsen's third offering but only generated a breeze: 1-2. Larsen delivered again and Mitchell fouled the ball into the crowd along the third base side: 1-2. Strike three called: 27 straight, perfection! Larsen's perfect game is all the more remarkable when considering that he had been completely ineffective against Brooklyn as the game two starter. He was "yanked" off the mound with two out in the second inning. He had retired five, walked four and given up a hit. In his only other appearance against Brooklyn, game four of the 1955 series, the Dodgers had rocked Larsen for five runs in four innings. In his perfect game, Larsen only went to a three ball count on one batter, Brooklyn shortstop Pee Wee Reese. The second batter of the game, Pee Wee was called out on a 3-2 pitch. |

In the first 90 years of

World Series play, the Series went the maximum number of games 32 time.

Most of those final games were not very close or reportedly very exciting.

Only 11 games were decided by one run. Of those 11, game seven of the 1960

Classic between the New York Yankees and the Pittsburgh Pirates stands out

as one of the most exciting games. In the first 90 years of

World Series play, the Series went the maximum number of games 32 time.

Most of those final games were not very close or reportedly very exciting.

Only 11 games were decided by one run. Of those 11, game seven of the 1960

Classic between the New York Yankees and the Pittsburgh Pirates stands out

as one of the most exciting games.

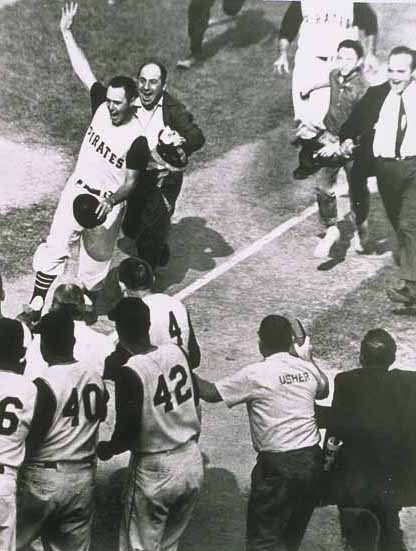

In the bottom of the first inning, Rocky Nelson's home run for the Bucs, with Bob Skinner on first base, gave the Pirates and the Forbes Field faithful an early lead: 2-0. But the 1960 Yankees were a potent offensive machine (on any field and in any social setting). Heading into game seven, the Yankees had won their three games by a combined score of 38-3, and, the now widely publicized drinking binges of Yankee players Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, Bill "Moose" Skowron, et al., offended many Quakerminded Pennsylvanians in the Pittsburgh region. The Pirates add two second inning runs before the Yanks could figure out Pirate starting pitcher Vern Law. Law, the 1960 National League Cy Young Award winner, had held the Bronx Bombers to just two singles over the first four frames, but in the fifth, Yankee first baseman Bill Skowron rocked a solo home run. In the sixth inning Law was yanked by Pirates' skipper Danny Murtaugh who summoned Roy Face from the bullpen. Before Face could end the inning, Yogi Berra had a three run homer and the Yanks had a 5-4 lead. After the top of the eighth, the Yanks had a 7-4 lead, but the Pirates were 1960's comeback kids. Twenty-eight of the Pirates 95 wins in 1960 were come-from-behind victories in which the Pirates were behind after six innings or later. Now the Pirates needed their biggest comeback of the year. They were three runs down with only six outs to go. Murtaugh's managerial intuition told him to send up an Italian, pinch-hitter Gino Cimoli responded with a single. The next batter, Bill Virdon (heritage of undetermined type), hit a sure double-play bouncing grounder to short. Yankee shortstop, Tony Kubeck moved up on the ball, then back, then up again, then back again (we're not making this up, he was really indecisive-rumor has it Kubeck would take hours to order from a menu), finally, the ball found Kubeck, but Kubeck's glove was elsewhere. The ball bounced wickedly off of Kubeck's throat (I swear, I'm not ad-libbing here), and instead of two outs, Muraugh's survivors had two runners on base and no outs. Dick Groat, the National League batting champ and M.V.P. in '60, ripped a single that plated Cimoli: 7-5. A sacrifice bunt moved the runners to second and third before Nelson popped out. With two down and two on, Roberto Clemente, who had gone hitless in the game, stepped to the plate. The future Hall-of-Famer legged out an infield single that scored Virdon: 7-6. Hal Smith then connected for a three-run home run that put the Pirates up 9-7. In the top of the ninth Murtaugh's managerial intuition must have been on the blink. Despite the fact that the Yankees had tagged Bob "Where Do You Want It" Friend for eight runs in his earlier outing, Friend was brought in to serve the Yankee bats. Picking up where they left off the last time they faced Friend, New York's Bobby Richardson and Dale Long hit back-to-back singles and Friend took a familiar seat on the bench. Murtaugh brought in Harvey Haddix. After one out, Mickey Mantle singled in Richardson: 9-8. Berra then grounded out to first, but when the Bucs tried to double up Mantle, the slugger outfoxed the Pittsburgh infield by hurrying back to first. Mantle's quick thinking allowed Long to score and left Mantle on base as the go-ahead run: 9-9. However, the Pirates retired the side and went to the bottom of the ninth. Bill Mazeroski, one of the games best glove men, was the Pittsburgh lead-off hitter. HOME RUN: 10-9! Game over. Pirates win. Bill Mazeroski's lead-off hom run had sunk the Yankee juggernaut. Better known for his excellent defensive abilities, Mazeroski had hit what remains perhaps the most dramatic home run in World Series history. It was the second homer of the Series for the slender second baseman, whose two-run shot plated the winning run in game four. Mazeroski crossed the plate in game seven with the World Series winning run, one of only 27 by the Pirates, compared to NewYork's seven game total of 55-over a two-to-one margin. The Yanks out-homered the Bucs 10-4, out-hit the Bucs 91-60, and the New York hurlers combined for an E.R.A. that was less than half of that compiled by Pittsburgh's mound corps, .354-.711. Despite New York's statistical dominance, Murtaugh's Pirates claimed the 1960 World Series title. |

The

sun shone a little brighter, the birds flew a little higher, and the

children's smiles were a little wider. 1972, truly was the summer of Reds

content, as the mighty Big Red Machine not only wantonly squashed all

comers in the National League, but also, in the eyes of Baseball's purist

puritan purists, Cincinnati's Reds upheld the decency of America by going

to bed early, abstaining from any display of facial hair (unlike Oakland's

mustachioed commie-hippie-dopeheads), and displaying good health and moral

virtue by refraining from smoking (despite the more than 600 gallons of

tobacco juice that would end up on the dugout floor after every game). The

sun shone a little brighter, the birds flew a little higher, and the

children's smiles were a little wider. 1972, truly was the summer of Reds

content, as the mighty Big Red Machine not only wantonly squashed all

comers in the National League, but also, in the eyes of Baseball's purist

puritan purists, Cincinnati's Reds upheld the decency of America by going

to bed early, abstaining from any display of facial hair (unlike Oakland's

mustachioed commie-hippie-dopeheads), and displaying good health and moral

virtue by refraining from smoking (despite the more than 600 gallons of

tobacco juice that would end up on the dugout floor after every game).

Yes, truly the Cincinnati Reds were the pinnacle of Baseball evolution. They were shining examples of how discipline, order, prayer, and 6.5 glasses of milk per day can turn a group of boys into fine, respectable men. Men that were going to roll to Series title after Series title, and humbly give credit to everyone but themselves. Such was the plan in 1972. It was the Reds' plan, it was America's plan, and if you ask the P.R. folks at Riverfront Stadium, it was fully endorsed by the Pope. Everybody knew it and everybody accepted it. Well, almost everybody. Everybody except the Oakland A's.

When a sportswriter is afraid to tell the truth about just how lawless a baseball team is, the adjetive "colorful" tends to get beaten into the ground. In 1972, calling the A's "colorful" was akin to saying that policemen enjoy an occasional doughnut, Richard Nixon inspired some trust issues, or Raquel Welch was "cute." The A's didn't get along with each other, let alone the members of other teams. If team owner (read: gang leader) Charlie Finley would have tried to implement a set of "haircut guidelines" as was done, and willingly (read: gutless) adhered to by Reds players, or demanded that the players return to their hotel rooms before 2:00 AM (without tequila, no less), you could probably found Finley in the Jimmy Hoffa Suite beneath the Oakland Coliseum. But then with Finley in charge, discipline wasn't a problem-there wasn't any. How could Charles Oscar Finley demand that his players display a pleasant demeanor toward societal norms when he was an outlaw himself? Just how incorrigible were the 1972 Oakland A's? Unconfirmed reports have members of the '72 Boston Bruins (who in '71-'72, combined for an NHL-high 3000 penalty minutes) visiting the A's training camp that year were "sickened" by the players.

The Series went the full seven games, with six of the games decided by one run. Oakland's Joe Rudi was the hero of the A's game two 2-1 victory with a home run and a one of the greatest game saving catches in Series history. Rudi leaped against the left field wall to rob Reds third baseman Dennis Menke of a ninth inning extra base hit. Cincinnati had more doubles (8-4), triples (1-0), runs (21-16), and RBI (21-16), and a lower ERA (2.17 - 3.05) than Oakland, but Oakland had one more win and an unlikely hero. A's catcher Gene Tenace, fresh off a .225 regular season and a blistering 1 for 17 performance in the ALCS, smashed a home run in his first World Series at-bat-after which he received a hero-sized wedgie from his teammates for "not hitting it far enough." Tenace then sent the entire city of Cincinnati into "denial therapy" when he ripped another home run in his second Series at-bat-after which even his own teammates were too stunned to administer a second., even more severe wedgie. Tenace-the-Menace went on to crush 4 Series home runs, hit .348, drive in 9 runs, steal the 8-track player and six polyester suits from Johnny Bench's Valiant in the Three Rivers Stadium parking lot (actually, that hasn't been confirmed), and capture the World Series MVP award. As a side note: unconfirmed reports did discover that the Sports Book at Caesar's Palace took a bet in early October for a "P. Roze" for $20,000 on the A's... you don't think? |

© Bucketfoot Baseball Publications, 1996

They were dubbed the "Swingin' A's," ostensibly, because of

their collective proficiency at the plate, but more realistically, because

they were always swingin' their fists at each other. This team had

bench-clearing brawls during spring training intra squad games.

This wasn't a team, it was a poor mannered gang in white

cleats.

They were dubbed the "Swingin' A's," ostensibly, because of

their collective proficiency at the plate, but more realistically, because

they were always swingin' their fists at each other. This team had

bench-clearing brawls during spring training intra squad games.

This wasn't a team, it was a poor mannered gang in white

cleats.

With Reggie "I Love Me" Jackass (I mean Jackson) unable to

play due to a torn hamstring, and thus watching the Series with all his

friends (read: alone), the Reds were expected to treat the Bay Area Bowry

Boys like Rush Limbaugh treats an all-fried buffet line. Absolute carnage

and devastation was the order of the day. But what materialized was one of

the closest and most exciting World Series ever played.

With Reggie "I Love Me" Jackass (I mean Jackson) unable to

play due to a torn hamstring, and thus watching the Series with all his

friends (read: alone), the Reds were expected to treat the Bay Area Bowry

Boys like Rush Limbaugh treats an all-fried buffet line. Absolute carnage

and devastation was the order of the day. But what materialized was one of

the closest and most exciting World Series ever played.